Thursday September 24th

As we had been unable to visit all the planned places yesterday because of the demonstration and because of the streets blocked off in readiness for the Berlin Marathon at the weekend, our tour leader took us on a walk round some of the sights. We walked from our Hotel up to the Tiergarten, an urban public park located in the middle of the city. It's huge, apparently 210 hectares or 520 acres, and dates back to1527 when it was founded as a hunting area for the king. It has far more trees that Hyde Park in London, so from the outside it looks more like a forest. We only had time to walk round the outside, as we were making for the Holocaust Memorial which is, of course, a memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust.

The memorial is on a big sloping site - 4.7-acres - covered with 2,711 concrete slabs arranged in a grid pattern. The slabs are big. They are all about 8 feet long by 3 ft wide but they vary in height from 8 inches to almost 16 feet. They are organized in rows, some of them going north–south, and others heading east–west at right angles.

They are apparently designed to produce an uneasy, confusing atmosphere, aiming to represent a supposedly ordered system that has lost touch with feelings of humanity, and it certainly is an odd place. If you go right in, it's like a maze and you can quickly get disorientated and lost among the high stones. Some people have also remarked on its resemblance to a cemetery.

We went on to the Reichstag building, but it was impossible to get a better photo than the one I took yesterday. There were stands being built, probably something to do with the marathon, and the whole area was cordoned off so photos were spoiled by the fences and obscured by the stands. I was glad I had managed a decent photograph yesterday.

Not far away is the Brandenburg Gate, probably one of the best-known landmarks in Germany, an 18th-century neoclassical triumphal arch, built on the site of a former city gate that marked the start of the road from Berlin to the town of Brandenburg an der Havel. It was commissioned by King Frederick William II of Prussia as a sign of peace and built between1788 and 1791.

On top of the gate is the Quadriga, a chariot drawn by four horses. The gate was originally named the Peace Gate and the goddess is Eirene, the goddess of peace.

I stood on an open square called Pariser Platz to take this photo. Up until 1989, I would have been standing in East Berlin to take this photo - except I couldn't have stood there at all, it was no man's land between the two walls, and just a wasteland of gravel and weeds.

The gate is nowadays restored to what it once was, the monumental entry to Unter den Linden, the famous avenue of linden trees, which originally led straight to the city palace of the Prussian monarchs. (In England, I am told we call them Lime trees.) Apparently, Duke Frederick William wanted to spruce up the route from his home to the Tiergarten hunting ground, so he ordered the planting of long rows of Linden trees, which would not only beautify Berlin but would also keep his route to the Tiergarten shady.

Nearly a century later, King Frederick II expanded the avenue by adding a collection of cultural buildings to the area, including the national opera house and the national library, making Unter den Linden larger and more prestigious, and it became a popular gathering place. It doesn't look too prestigious at the moment I'm afraid, since it's full of cranes and hoardings and huge holes, all connected with the building of new subway lines and stations. It's planted with four rows of Linden trees, about a thousand in total. I read somewhere that Hitler had them all cut down and replaced with Nazi standards, but it was so unpopular he replaced them. It's hard to think of Hitler caring about his unpopularity!

Unter den Linden is a long street, stretching 1.5 kilometres from Pariser Platz to the Palace Bridge near Museum Island, and we walked right along it to where the Royal Palace is being re-built. It will be a replica of the original Royal Palace, so Unter den Linden will once again lead from the Brandenburg Gate to the Royal Palace.

We stopped off at Bebelplatz again to see if we could photograph the memorial to the book burning this time, but it was behind a hoarding; it seems that the whole of the centre of Berlin is being re-built at present. It was a pity to miss the plaque, which includes a line from a play by Heinrich Heine, which translates into English as: ’That was only a prelude; where they burn books, they will in the end also burn people'.

When we finally reached Museum Island, I wanted to go to the Pergamon Museum, but it was closed, to my great chagrin. I've wanted to go there since I visited Pergamon itself in 1975, so I was really upset not to be able to see it. I thought briefly of visiting the Egyptian Museum to see the head of Nefertiti, but Paul wasn't keen, and we couldn't find good information about which Museum would be best for paintings, as things seem to have been moved about a good deal. So we decided to visit the Museum of German History, of which we had heard good reports.

This museum is housed in what used to be the Zeughaus arsenal, the oldest building on Unter den Linden, built between 1695 and 1706, and absolutely enormous. We decided to concentrate on the ground floor, which deals with the history of Germany between 1918 and the re-unification in 1989.

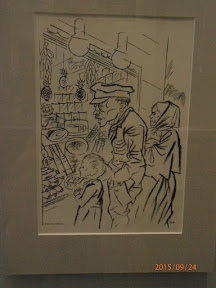

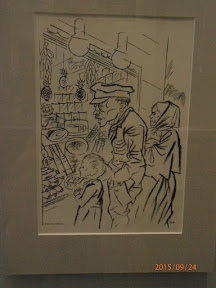

We began with the period after 1918, when the victor nations in World War I decided to assess Germany for their costs of conducting the war against them, and most German people suffered great hardship. This cartoon by George Grosz, shows the average German family looking hungrily through the delicatessen window at the food they couldn't afford.

George Grosz was a German artist known especially for his caricatural drawings and paintings of Berlin life in the 1920s. He was a prominent member of groups like the Berlin Dada during the Weimar Republic, before wisely emigrating to the United States in 1933. The Nazis didn't like those who caricatured them!

With no means of paying the reparations demanded, Germany printed money, causing the value of the Mark to collapse. Between 1914 and the end of 1923 the German mark’s rate of exchange against the U.S. dollar plummeted. In 1914, $1 was worth 4.2 marks; in 1923, $1was worth 4.2 trillion marks. It was said that many Germans carted wheelbarrows of cash to the shops to pay for their groceries.

During this hyperinflation, higher and higher denominations of banknotes were issued. Before the war, the highest denomination was 1000 Marks, equivalent to approximately £50 or $238. In early 1922, 10,000 Mark notes were introduced, followed by 100,000 and 1 million Mark notes early in 1923, then later notes up to 50 million Marks. The hyperinflation peaked in October 1923 and banknote denominations rose to 100 trillion Marks. This is a heap of some of these very high denomination notes.

At the end of the hyperinflation, these 100 trillion Mark notes were worth approximately £5 or $24.

The chaos in Germany lead to failures in Government, coups and attempted coups, and ultimately, the rise of the Nazis. I could fill this post with photos I took of posters of Hitler, exhortations to the populace about how to behave and so on, but I'll just content myself with showing the way National Socialism tried to permeate every aspect of people's lives. This is a child's Doll's House.

It may look fairly ordinary at first sight, but the wallpaper is covered in images of children taking part in Hitler Youth activities, and actually the whole house is decorated with posters and photographs of Hitler and other Nazi grandees. You could buy toy cars with Hitler in them, and children were encouraged from an early age to venerate Hitler and conform to National Socialist ideals.

There were many images from the war, though not perhaps as many as you might think. I like this photo of the Enigma machine.

An Enigma machine was actually a series of cipher machines developed and used originally for both commercial and military usage. Early models were used commercially from the early 1920s, and adopted by the military and government services of several countries, most notably Nazi Germany.

By the time we had got to the end of the section on the war, we were both a bit tired, but we had a brief look at the period between 1945 and re-unification. There were a lot of information boards on the politics involved, but to my mind the most interesting displays were those contrasting the different material goods available to people in West and East Germany.

The West German consumer goods included the famous VW Beetle. The East German equivalent, of course, featured the Trabant.

The Trabant was the most common vehicle in East Germany, and it was also exported to other countries. It had an outdated and inefficient two-stroke engine so it had poor fuel economy and produced a thick, smoky exhaust. It was designed with a steel frame and a body made of Duroplast. Duroplast was a hard plastic (similar to Bakelite) made of recycled materials. This could well have been responsible for the popular misconception that the Trabant was made of cardboard. Although more than three million were made, production could not keep up with demand, and many people had to wait years for one!

By this time, we had spent about 4 hours in the Museum and both of us were exhausted. It would have been nice to look at the earlier German History on the upper floor, but we didn't have the stamina. We had no information about public transport, so we walked all the way back along Unter den Linden, all round the Tiergarten and back to our hotel, arriving around 5 o'clock. After this, we were fit for nothing and just ate in the hotel before packing for our journey home.

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPad